Inside the Garmin cyberattack - Anatomy of the WastedLocker ransomware

Originally published July 29th, 2020 as an interview on Cycling Tips, with Matt de Neef

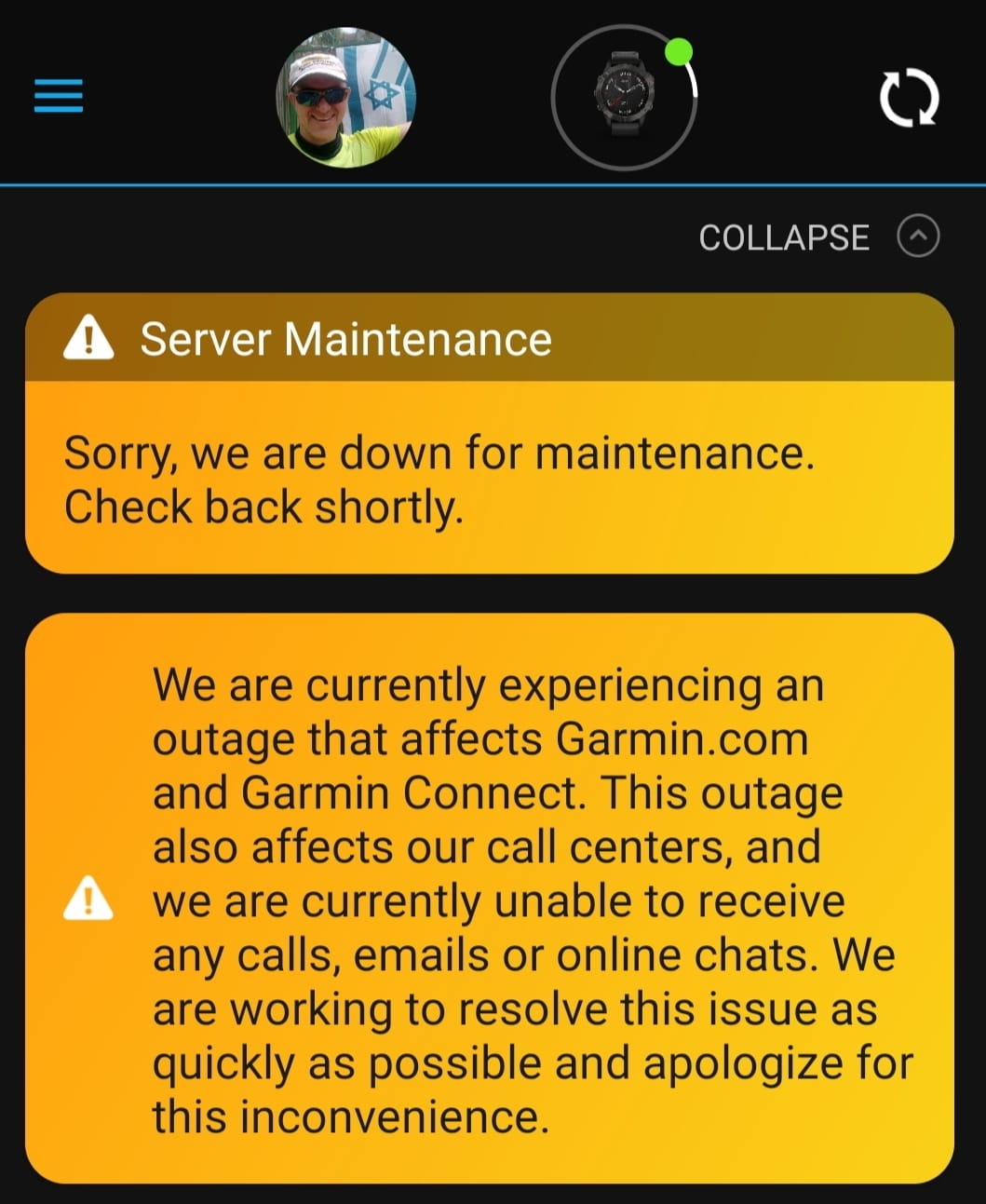

Cyberattacks can be personal. On Thursday, July 23rd, Garmin experienced a massive WastedLocker ransomware attack, effecting millions of worldwide users. As of writing, they still haven’t resumed normal operations. Activities can’t be synced, and if it wasn’t uploaded to Strava… did it take place? Beyond App connectivity, Garmin is reportedly experiencing a company-wide disruption, shutting down support centers and manufacturing. It’s emerging that even “standalone” devices are being affected, with reports that watches are experiencing tracking glitches, and failures saving activities.

While frustrating for sports users, implications can be much further reaching.

Has the integrity of privacy data and training history been compromised? What about Garmin’s mission-critical Aviation and Naval navigation system? The flyGarmin service used by pilots is reportedly down.

What happened? We’ve all heard of or experienced a ransomware attack. You open an inconspicuous email attachment, and before knowing it, your files are encrypted. These can sometimes be restored using backups, or by paying the ransom, usually in Bitcoin. Victims often testify that ransomware actors have excellent customer service. Really. It’s called RaaS, Ransomware As A Service.

Enterprises suffer on a much larger scale. Since early 2019 there’s been a shift in the pattern of attacks, especially against manufacturing companies and public utilities. While the primary motive of the attacks remains financial gains, the current trend is “wiper” attacks aiming to severely disrupt operations. It’s what happened with automotive giant Honda, and bike manufacturer Canyon. The X-Mas timing of the Canyon attack wasn’t a coincidence.

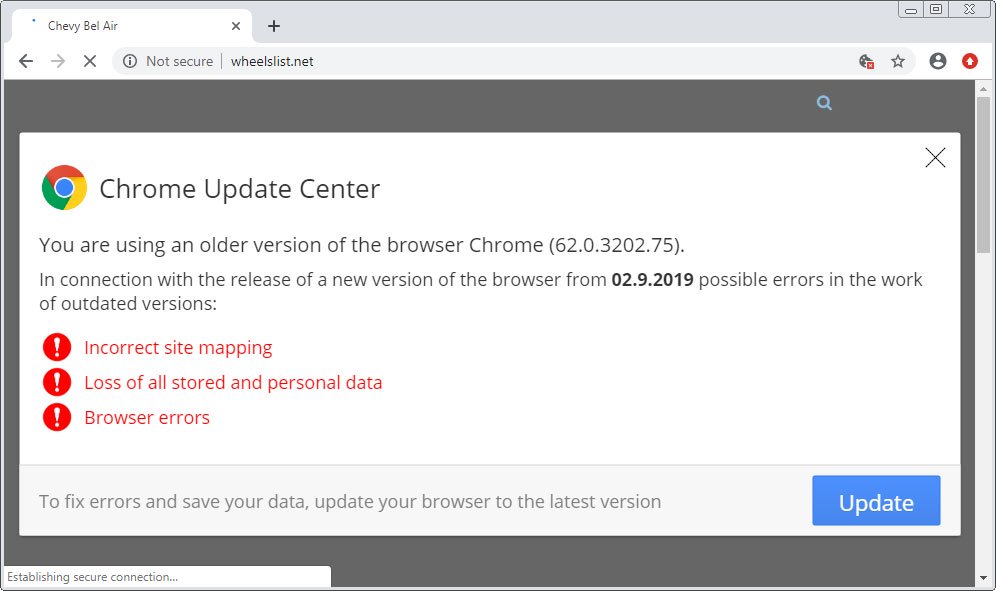

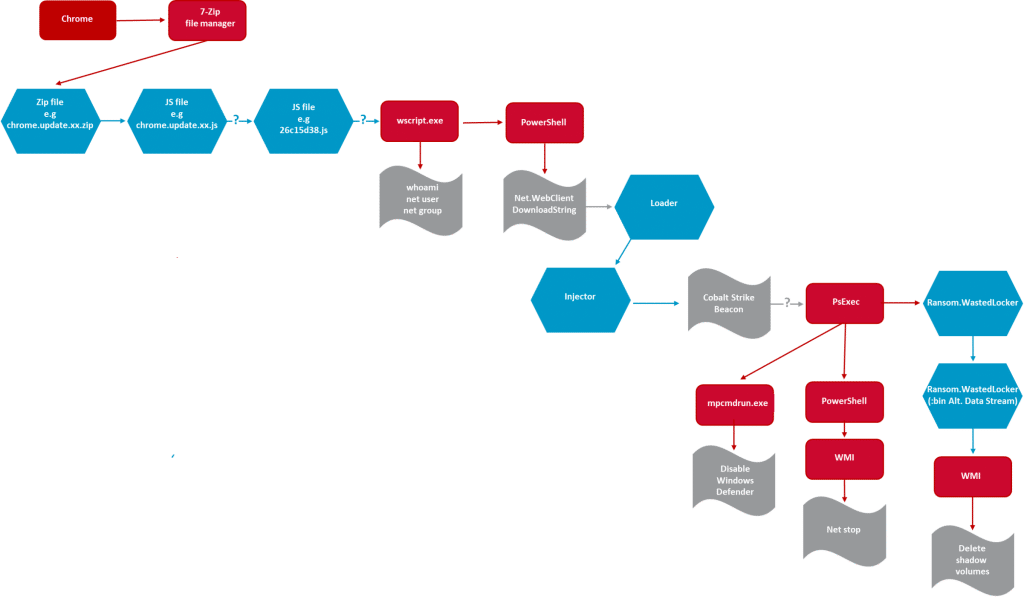

The disruption is achieved using a multi-staged attack. It often starts via browsing a compromised legitimate website, using fake software update alerts. Another common method is via a phishing email, luring employees to open a weaponized document. Files uploaded via supply-chain processes can also be used. These contain mutated versions of known threats, capable of evading AV scans.

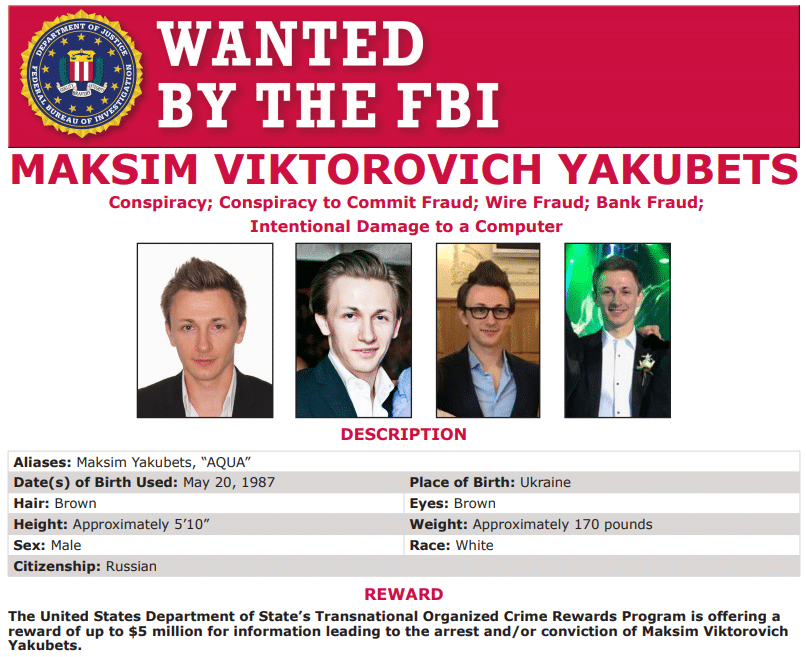

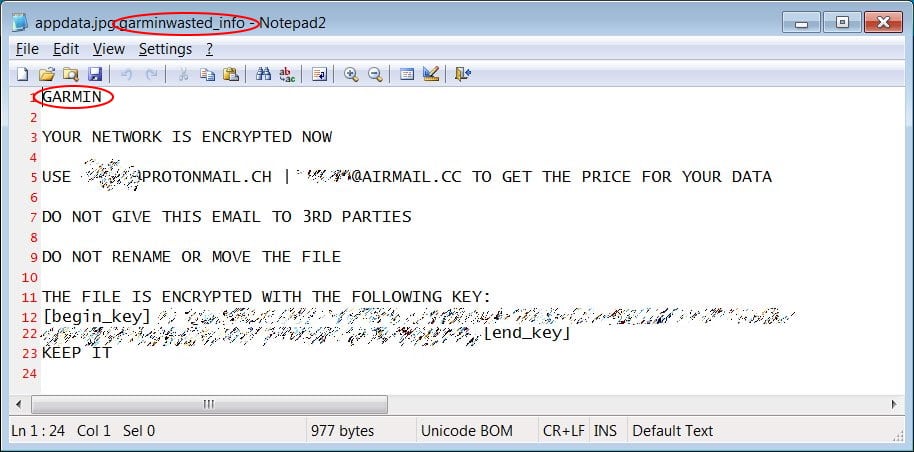

With Garmin, it’s confirmed to be a WastedLocker ransomware, linked to the Russian based hacker group known as Evil Corp, that’s been sanctioned by the US Treasury.

Once the initial attack “vector” is achieved, a complex sequence of events begins. Threat actors target specific organizations, learning how their network can be exploited, and use the weaknesses to affect virtually all the victim’s endpoints and servers. Commercial penetration test tools such as Cobalt Strike are used. Propagation is typically achieved using a “worm” component, enabling to bridge from “office” networks into the “production” environment (Manufacturing/OT/ICS network). In many incidents the interruption of business processes is sufficient to impact manufacturing, causing severe financial damages. The duration of the incident from initial compromise until the activation of the ransom component can last several weeks. During that time, attackers use the achieved on the network to exfiltrate information.

Once this has been achieved, the ransom component is activated in an orchestrated way to achieve rapid enterprise- wide disruption, serving as a final revenue stream for the attackers. While attackers demanded, and received, $10 million from Garmin, a study of recent WastedLocker incidents reveals they didn’t contain a data exfiltration component.

Another differentiator of the Garmin incident is their public relations handling. Garmin has released limited information, perhaps due to their upcoming quarterly earnings report. Other companies decided that transparency is a better strategy to maintain trust. An example is the ransomware attack against aluminum manufacturer Norsk Hydro, with their CIO leading a series of press conferences and media announcements on their incident containment and recovery efforts.

Manufacturing companies need to actively understand and create a plan to address these “wiper” ransomware attacks, since they have been a primary target. Industrial Cybersecurity specific risks should be assessed, and preventative mechanisms implemented. Since a primary attack vector is downloading malicious files, these should be inspected on the perimeter, before arriving to endpoints. Content Disarm and Reconstruction (CDR) is a technology that uses highly optimized detection tools to do the best possible to pre-filter malicious files. Yet, CDR assumes this step can fail and proceeds to “disarm” the files, to ensure users receive a harmless copy. This is especially effective for “productivity” documents such as everyday PDF and MS-Office files. It also reduces the reliance on employees as serving as a line of defense against phishing attacks.

Organizations must also accept that security incidents are inevitable yet shouldn’t be a catastrophe. Network separation contains incidents and prevents attacks from propagating into the manufacturing environment. Next generation endpoint detection and OT/ICS network monitoring should be deployed to alert and block anomalous activities.

Finally, until Garmin is back online, wait before scrambling to “manually” upload activities. Don’t plug your Edge or favorite watch into your office computer. IoT’s (internet of things) can be compromised and attack via the USB connection.

If your Garmin device doesn’t display distance during the activity or appears to be stuck on the “Saving” or “Discarding” screen after the activity, or if the time isn’t syncing, then check out these trouble shooting steps here, and here.

The light at the end of the tunnel? Every company has or will have their incident. They recover. So will Garmin.

By: Oren T. Dvoskin, Global Marketing Director, Sasa Software